A quarterly publication of Society of Workforce Planning Professionals

Multi-Site Operations: Challenges and Options

By Maggie Klenke

Managing the staffing for a single-site contact center is daunting enough with skill-based routing (SBR) and today’s multi-media interactions. Moving to a multi-site configuration can make it even more challenging. Whether your company is opening another site, has added a center through acquisition, or hired an outsourcer to handle part of the load, allocation of the work among the sites will be required.

Components of Multi-Site Operations

Let’s start with the basic operation of a single site contact center. There are likely to be different kinds of contacts that need to be handled. In an ideal world, all agents would be able to handle any type of contact that arrives. But in today’s center, it is more likely to have agents with a mix of different skills so that some might handle only calls, or only email, while others might handle both or all work types in the same operation. This is supported by a skill-based routing process that requires forecasting for each type of work separately and then scheduling based on the unique combinations of skills present within the agent team.

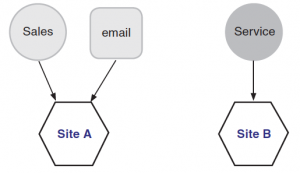

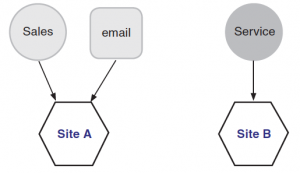

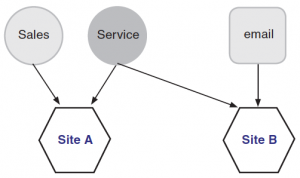

Now we are going to add a second site to our operation, but it will be assigned to handle only the service calls. All sales calls and email will still go to Site A and all service calls to Site B. While this is a multi-site operation, it is essentially managed as two single sites as each receives a unique set of workload and there is no cross-over of work or agents. We can change the skills by site so that calls go to Site A and email to Site B, but as long as all of a work type is handled in one site and there is no cross-over, it is essentially a single-site operation for each site.

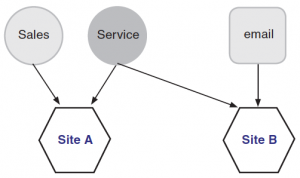

In the next configuration, we have added a new component. Service calls will be handled in both sites while sales calls and emails will each be handled separately at a single site. Now we have a single work type being shared between the sites and this changes everything. Some of the agents at Site A may do only one call type and others handle both. Agents at Site B may only handle service calls, others doing email, and some both. Any scheduling process must consider both the distribution of the workload between the three types of work, but also the skills available among the staff at each site during each interval.

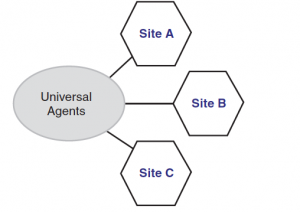

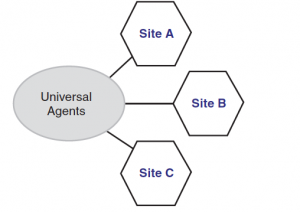

In the third type of operation, we have three sites but they all share all workload. The agents in every site have skills that cover all work types (although any individual agent may have only some of the skills).

There are clearly benefits to this type of operation. The sites may be located in different time zones or even around the globe so that operations can be configured for “follow the sun” distribution. This means, for example, that a site in America might handle calls during the daylight hours but shut down at night, routing all calls to the Asia site, where it is daylight for them. No one is required to work the night shift. Recruiting staff may be easier if the total complement of staff does not have to come from a single city. Skills may also be more available in different locations, especially those involving languages. Labor costs can also vary considerably depending on location. Any type of emergency that might affect one site (such as a weather pattern) is less likely to take out all sites so that operations can be continued.

Challenges of Multi-Site Operations

There are several typical steps involved in the workforce management process. Let’s explore how these might be different in a multi-site operation versus a single site.

We want to accommodate the organization’s ability to centralize or distribute decision-making and management processes in whatever way the current management desires. There is no “best practice” configuration, just the one that fits the organization’s desires and capabilities best at that time. Some companies have a strong bias toward centralization while others prefer more local autonomy. Where growth of the number of sites has resulted from acquisitions, the decisions may be even more complex. And the management desire for centralization or decentralization can often change with new personnel, making flexibility to adjust beneficial.

Complicating Factors

Before we can begin the WFM process, we need to look at some of the complicating factors that may impact the decisions. In some multi-site operations, the telephone system will be a single system with distributed components (or operation in the cloud) so it operates as if it is all in the same room. Others may have more than one system in their sites, but they are all the same make and model from a single vendor. Yet others will have multiple vendors and different systems handling the calls. The same is true of the WFM systems. There can be a single distributed system or operation in the cloud, multiple systems from the same vendor, or a mix of different WFM systems. The latter is especially likely when the company has grown through acquisition.

The challenge of systems from different manufacturers, or even different models from the same vendor, is that the processes, calculations, and reporting options may vary. Making them operate on a unified basis across sites may be complicated and frankly nearly impossible in some situations. Any limitations that exist need to be well understood before the WFM process allocation decisions can be made.

Another complication can come from the placement of the IVR systems within the configuration. Some are at individual sites while other capabilities may be at the network level. The same is true of the call routing devices. These are typically used to connect a distributed set of components to make them operate with a centralized decision tree for routing the contacts. These can be particularly useful in a configuration that has multiple manufacturers’ ACD systems.

Another challenge to be considered is the networks that will deliver the workload to the sites and agents. Many companies rely on toll-free services to bring in their calls, but others also have local phone numbers that support customers in the areas around the sites. These may be more complicated to route to multiple locations than the toll-free calls.

Email systems and websites can also be centralized or distributed and may be the same or different manufacturers. Linking these disparate systems together to make them operate and distribute workload as desired may be complex.

There are any number of unique local operations that can complicate the processes. One of the benefits of multiple sites is being able to limit the hours of operation and some or all of the sites. There may be one site in the network that is 24 X 7 for example, with others able to limit schedules to a 10 or 12 hour timeframe.

The operation may include unions or other bargaining units and it is not unusual for there to be different agreements for each site or even to have a mix of union and non-union shops within the network. Accommodating the unique rules for each site can certainly be challenging. There may also be benefit differences such as number of days off that will need to be considered.

Local management may want to take control of their own operation to a larger or smaller extent, and the ability of that local staff to step up to the desired responsibilities may also vary. Creating a distributed WFM staff may have its own challenges, and the team is likely to require more people decentralized. Cross-training and ensuring coverage of all with WFM responsibilities may also be more difficult if they are not in one shop.

Part-time staff may be easier to find in some locations making the allocation of full- and part-time schedules uneven. This can create motivational issues among the staff. Lunch length and break length and placement rules may vary by site depending on on-site cafeterias and other factors. And there is always the “we’ve always done it this way” issue to consider as well.

WFM Process Steps

Let’s start with the processes that go into creating the forecast. First, remember that a separate forecast is needed for each unique work type or skill whether it is all done in one site or distributed. Gathering the historical data means tapping into all systems in all sites where that work has been handled. The process may require manual combinations of work that have been handled separately in the past. Volumes and handle times may vary by site. The drivers that increase or decrease workload may be localized or central. For example, a marketing campaign is likely to affect all sites that handle sales calls, but a weather-related change may only affect one site. Setting up the data gathering and validation process for ongoing accuracy may involve both central and local staff as the best information sources must be tapped.

Where any work type is shared across multiple sites, the forecast of volume must be created on a central basis. How the work is allocated among the sites will come later, but the total volume of that type must be understood on a combined basis. Where there are work types that are handled only in a single site of the network, the option to forecast locally or centrally is open to whatever will work best for the organization. It is also possible to forecast only the volume if the AHTs vary significantly by site, allowing each site to calculate the total workload that will need to be handled there.

Once the forecast is created, the next step is to calculate the staffing requirements. This can be done centrally or locally. Where the hours of operation vary, the workload may be allocated to each of the sites by interval, allowing the local operation to determine the staffing requirements by interval needed to handle it. However, the central team can calculate the total staffing requirements and then allocate those bodies in chairs requirements to each of the sites if preferred. This is the best option where skill-based routing is involved as the total staffing requirements can be calculated as the schedules are created, considering the available skills across the entire network.

Next comes creation of the schedules needed to meet the staffing requirements by interval. With SBR, the staffing and scheduling processes are often combined to ensure that the skills of the available staff are matched up to the forecast workload by skill as closely as possible. This can be done centrally or locally depending on how the allocation of work has been done. If the forecast was allocated to the sites, the sites will create the schedules. However, the total number and type of schedules across the entire network can be created centrally and this may be best if the skills available vary by site, but the scheduling rules are similar.

Once the schedules are created, it is time to match them up to the staff. If the schedules were created centrally, the central WFM team must consider the hours of operation, full- and part-time personnel, and the skills available at each site so that the allocated schedules can be matched up to the number and skills of the available agents at each site. If the schedules were created locally, these considerations are part of the schedule creation process.

Managing the planned schedule exceptions such as vacations, training, meetings, etc. is often done on a local basis, although it can be centralized if desired. The benefit of centralizing this process is that the central WFM team can consider the staffing across all sites to ensure coverage, find a trading partner, etc. If done locally, the local manager must ensure that their allocated schedules are covered within the site with no help from other locations.

As the workday arrives, the actual workload and staffing need to be monitored and adjustments made as needed to meet service goals. Where workload is shared among sites, this is often done on a centralized basis to allow for one site to make up a shortfall in another as needed. However, it can be done locally but all adjustments of staffing will have to be done within the available site staffing. Centralized processes can also reallocate the workload among the sites as needed while local processes generally do not have that option.

Finally, the results of the operation need to be reported. This is often a shared responsibility with each team reporting on those areas over which they have responsibility. The central team will generally need to roll up the totals for senior management to see the overall results, but local management may want to see their portion separately and feel the need to create those reports locally.

Local Responsibilities

One of the challenges that can cause angst among the managers in a multi-site operation is what is the responsibility of the local manager and who can be held accountable for the speed of answer goal. It is important to understand what each party is contributing and where each is just complying with the plans of others.

Let’s explore the various options for centralization and what local management can be held responsible for delivering.

- In the least centralized operation where work is shared between sites, the forecast is centralized, but then the workload volumes are distributed to the local sites. Each site is then responsible for creating a staffing plan for that workload, creating and assigning the schedules to the agents, managing any planned exceptions and the intraday processes. In this case, the local management is responsible for delivering the speed of answer results (assuming the forecast is reasonably accurate).

- In the second option where the central team calculated the staffing requirements and distributed a head count requirement to each site, the local personnel can take that staffing requirement by interval and create the schedules for the staff. In this case, if the local manager met the interval requirements of head count but the speed of answer goal is missed, it is not fair to hold the local manager responsible for the service. Therefore, the primary measure for local management is whether the interval requirements for head count are met.

- In the third case, the schedules are created by the central staff and the local management is responsible for assigning them to their staff. Matching up an agent to each of the schedules allocated to that site is the primary responsibility of the local managers, including managing planned exceptions and intraday adjustments. The primary measurement of local success is ensuring that every schedule is filled, and each interval has the planned staffing in place. Once again, they cannot be held responsible for service speed.

- In the fourth configuration, the centralized staff creates the schedules and assigns them to the local staff at each site. The local managers must manage planned exceptions and intraday adjustments, but their goal is to ensure that the assigned staff are in place or a substitute has been found.

- The most centralized operation is one in which all WFM processes are centralized including the management of intraday adjustments. In this case, the local management is responsible to ensure that the planned staffing is in place at their site, and that they complete any adjustments that are required to meet the intraday changes.

Summary

There are a myriad of options that can be applied to the distribution of WFM tasks in a multi-site operation. Understanding any technology limitations is a factor to consider before the best allocation scheme can be selected. It is also common for the distribution of work and responsibilities to change over time as management personnel change, as there is no “best practice” configuration. Whether the configuration is comprised of all in-house centers or includes an outsourcer, the options are essentially the same. However, the contractual agreement between client and outsourcer may guide the decision on the best allocation method.

Maggie Klenke is one of the founders of The Call Center School (now retired) and an active industry consultant, assisting contact center clients in development of strategic and tactical plans, technology applications, forecasting and scheduling optimization, service level analysis, and overall management issues. She may be contacted at maggie.klenke@mindspring.com or 615-651-3324.

Multi-Site Operations: Challenges and Options

By Maggie Klenke

Managing the staffing for a single-site contact center is daunting enough with skill-based routing (SBR) and today’s multi-media interactions. Moving to a multi-site configuration can make it even more challenging. Whether your company is opening another site, has added a center through acquisition, or hired an outsourcer to handle part of the load, allocation of the work among the sites will be required.

Components of Multi-Site Operations

Let’s start with the basic operation of a single site contact center. There are likely to be different kinds of contacts that need to be handled. In an ideal world, all agents would be able to handle any type of contact that arrives. But in today’s center, it is more likely to have agents with a mix of different skills so that some might handle only calls, or only email, while others might handle both or all work types in the same operation. This is supported by a skill-based routing process that requires forecasting for each type of work separately and then scheduling based on the unique combinations of skills present within the agent team.

Now we are going to add a second site to our operation, but it will be assigned to handle only the service calls. All sales calls and email will still go to Site A and all service calls to Site B. While this is a multi-site operation, it is essentially managed as two single sites as each receives a unique set of workload and there is no cross-over of work or agents. We can change the skills by site so that calls go to Site A and email to Site B, but as long as all of a work type is handled in one site and there is no cross-over, it is essentially a single-site operation for each site.

In the next configuration, we have added a new component. Service calls will be handled in both sites while sales calls and emails will each be handled separately at a single site. Now we have a single work type being shared between the sites and this changes everything. Some of the agents at Site A may do only one call type and others handle both. Agents at Site B may only handle service calls, others doing email, and some both. Any scheduling process must consider both the distribution of the workload between the three types of work, but also the skills available among the staff at each site during each interval.

In the third type of operation, we have three sites but they all share all workload. The agents in every site have skills that cover all work types (although any individual agent may have only some of the skills).

There are clearly benefits to this type of operation. The sites may be located in different time zones or even around the globe so that operations can be configured for “follow the sun” distribution. This means, for example, that a site in America might handle calls during the daylight hours but shut down at night, routing all calls to the Asia site, where it is daylight for them. No one is required to work the night shift. Recruiting staff may be easier if the total complement of staff does not have to come from a single city. Skills may also be more available in different locations, especially those involving languages. Labor costs can also vary considerably depending on location. Any type of emergency that might affect one site (such as a weather pattern) is less likely to take out all sites so that operations can be continued.

Challenges of Multi-Site Operations

There are several typical steps involved in the workforce management process. Let’s explore how these might be different in a multi-site operation versus a single site.

We want to accommodate the organization’s ability to centralize or distribute decision-making and management processes in whatever way the current management desires. There is no “best practice” configuration, just the one that fits the organization’s desires and capabilities best at that time. Some companies have a strong bias toward centralization while others prefer more local autonomy. Where growth of the number of sites has resulted from acquisitions, the decisions may be even more complex. And the management desire for centralization or decentralization can often change with new personnel, making flexibility to adjust beneficial.

Complicating Factors

Before we can begin the WFM process, we need to look at some of the complicating factors that may impact the decisions. In some multi-site operations, the telephone system will be a single system with distributed components (or operation in the cloud) so it operates as if it is all in the same room. Others may have more than one system in their sites, but they are all the same make and model from a single vendor. Yet others will have multiple vendors and different systems handling the calls. The same is true of the WFM systems. There can be a single distributed system or operation in the cloud, multiple systems from the same vendor, or a mix of different WFM systems. The latter is especially likely when the company has grown through acquisition.

The challenge of systems from different manufacturers, or even different models from the same vendor, is that the processes, calculations, and reporting options may vary. Making them operate on a unified basis across sites may be complicated and frankly nearly impossible in some situations. Any limitations that exist need to be well understood before the WFM process allocation decisions can be made.

Another complication can come from the placement of the IVR systems within the configuration. Some are at individual sites while other capabilities may be at the network level. The same is true of the call routing devices. These are typically used to connect a distributed set of components to make them operate with a centralized decision tree for routing the contacts. These can be particularly useful in a configuration that has multiple manufacturers’ ACD systems.

Another challenge to be considered is the networks that will deliver the workload to the sites and agents. Many companies rely on toll-free services to bring in their calls, but others also have local phone numbers that support customers in the areas around the sites. These may be more complicated to route to multiple locations than the toll-free calls.

Email systems and websites can also be centralized or distributed and may be the same or different manufacturers. Linking these disparate systems together to make them operate and distribute workload as desired may be complex.

There are any number of unique local operations that can complicate the processes. One of the benefits of multiple sites is being able to limit the hours of operation and some or all of the sites. There may be one site in the network that is 24 X 7 for example, with others able to limit schedules to a 10 or 12 hour timeframe.

The operation may include unions or other bargaining units and it is not unusual for there to be different agreements for each site or even to have a mix of union and non-union shops within the network. Accommodating the unique rules for each site can certainly be challenging. There may also be benefit differences such as number of days off that will need to be considered.

Local management may want to take control of their own operation to a larger or smaller extent, and the ability of that local staff to step up to the desired responsibilities may also vary. Creating a distributed WFM staff may have its own challenges, and the team is likely to require more people decentralized. Cross-training and ensuring coverage of all with WFM responsibilities may also be more difficult if they are not in one shop.

Part-time staff may be easier to find in some locations making the allocation of full- and part-time schedules uneven. This can create motivational issues among the staff. Lunch length and break length and placement rules may vary by site depending on on-site cafeterias and other factors. And there is always the “we’ve always done it this way” issue to consider as well.

WFM Process Steps

Let’s start with the processes that go into creating the forecast. First, remember that a separate forecast is needed for each unique work type or skill whether it is all done in one site or distributed. Gathering the historical data means tapping into all systems in all sites where that work has been handled. The process may require manual combinations of work that have been handled separately in the past. Volumes and handle times may vary by site. The drivers that increase or decrease workload may be localized or central. For example, a marketing campaign is likely to affect all sites that handle sales calls, but a weather-related change may only affect one site. Setting up the data gathering and validation process for ongoing accuracy may involve both central and local staff as the best information sources must be tapped.

Where any work type is shared across multiple sites, the forecast of volume must be created on a central basis. How the work is allocated among the sites will come later, but the total volume of that type must be understood on a combined basis. Where there are work types that are handled only in a single site of the network, the option to forecast locally or centrally is open to whatever will work best for the organization. It is also possible to forecast only the volume if the AHTs vary significantly by site, allowing each site to calculate the total workload that will need to be handled there.

Once the forecast is created, the next step is to calculate the staffing requirements. This can be done centrally or locally. Where the hours of operation vary, the workload may be allocated to each of the sites by interval, allowing the local operation to determine the staffing requirements by interval needed to handle it. However, the central team can calculate the total staffing requirements and then allocate those bodies in chairs requirements to each of the sites if preferred. This is the best option where skill-based routing is involved as the total staffing requirements can be calculated as the schedules are created, considering the available skills across the entire network.

Next comes creation of the schedules needed to meet the staffing requirements by interval. With SBR, the staffing and scheduling processes are often combined to ensure that the skills of the available staff are matched up to the forecast workload by skill as closely as possible. This can be done centrally or locally depending on how the allocation of work has been done. If the forecast was allocated to the sites, the sites will create the schedules. However, the total number and type of schedules across the entire network can be created centrally and this may be best if the skills available vary by site, but the scheduling rules are similar.

Once the schedules are created, it is time to match them up to the staff. If the schedules were created centrally, the central WFM team must consider the hours of operation, full- and part-time personnel, and the skills available at each site so that the allocated schedules can be matched up to the number and skills of the available agents at each site. If the schedules were created locally, these considerations are part of the schedule creation process.

Managing the planned schedule exceptions such as vacations, training, meetings, etc. is often done on a local basis, although it can be centralized if desired. The benefit of centralizing this process is that the central WFM team can consider the staffing across all sites to ensure coverage, find a trading partner, etc. If done locally, the local manager must ensure that their allocated schedules are covered within the site with no help from other locations.

As the workday arrives, the actual workload and staffing need to be monitored and adjustments made as needed to meet service goals. Where workload is shared among sites, this is often done on a centralized basis to allow for one site to make up a shortfall in another as needed. However, it can be done locally but all adjustments of staffing will have to be done within the available site staffing. Centralized processes can also reallocate the workload among the sites as needed while local processes generally do not have that option.

Finally, the results of the operation need to be reported. This is often a shared responsibility with each team reporting on those areas over which they have responsibility. The central team will generally need to roll up the totals for senior management to see the overall results, but local management may want to see their portion separately and feel the need to create those reports locally.

Local Responsibilities

One of the challenges that can cause angst among the managers in a multi-site operation is what is the responsibility of the local manager and who can be held accountable for the speed of answer goal. It is important to understand what each party is contributing and where each is just complying with the plans of others.

Let’s explore the various options for centralization and what local management can be held responsible for delivering.

- In the least centralized operation where work is shared between sites, the forecast is centralized, but then the workload volumes are distributed to the local sites. Each site is then responsible for creating a staffing plan for that workload, creating and assigning the schedules to the agents, managing any planned exceptions and the intraday processes. In this case, the local management is responsible for delivering the speed of answer results (assuming the forecast is reasonably accurate).

- In the second option where the central team calculated the staffing requirements and distributed a head count requirement to each site, the local personnel can take that staffing requirement by interval and create the schedules for the staff. In this case, if the local manager met the interval requirements of head count but the speed of answer goal is missed, it is not fair to hold the local manager responsible for the service. Therefore, the primary measure for local management is whether the interval requirements for head count are met.

- In the third case, the schedules are created by the central staff and the local management is responsible for assigning them to their staff. Matching up an agent to each of the schedules allocated to that site is the primary responsibility of the local managers, including managing planned exceptions and intraday adjustments. The primary measurement of local success is ensuring that every schedule is filled, and each interval has the planned staffing in place. Once again, they cannot be held responsible for service speed.

- In the fourth configuration, the centralized staff creates the schedules and assigns them to the local staff at each site. The local managers must manage planned exceptions and intraday adjustments, but their goal is to ensure that the assigned staff are in place or a substitute has been found.

- The most centralized operation is one in which all WFM processes are centralized including the management of intraday adjustments. In this case, the local management is responsible to ensure that the planned staffing is in place at their site, and that they complete any adjustments that are required to meet the intraday changes.

Summary

There are a myriad of options that can be applied to the distribution of WFM tasks in a multi-site operation. Understanding any technology limitations is a factor to consider before the best allocation scheme can be selected. It is also common for the distribution of work and responsibilities to change over time as management personnel change, as there is no “best practice” configuration. Whether the configuration is comprised of all in-house centers or includes an outsourcer, the options are essentially the same. However, the contractual agreement between client and outsourcer may guide the decision on the best allocation method.

Maggie Klenke is one of the founders of The Call Center School (now retired) and an active industry consultant, assisting contact center clients in development of strategic and tactical plans, technology applications, forecasting and scheduling optimization, service level analysis, and overall management issues. She may be contacted at maggie.klenke@mindspring.com or 615-651-3324.